-

Case Studies

-

- Rediscovering the Skies: Flight Simulator Brought to Life with GeoBox Technology

- Unlocking the Future of Learning

- Projection Based Immersive Learning: NOW and The Future of Education and Training

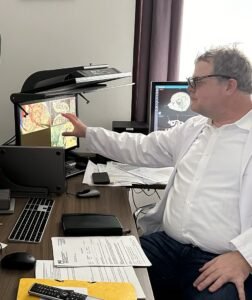

- GeoBox Unveiling the Future of Neurosurgery with 3D Technology: Interview Professor Wolfsberger (Austria)

- Creating large projection in School Theater for multiple purposes (Netherlands)

- Secta Immersive Enhances Trainings in Immersive Rooms with GeoBox

-

- GeoBox and Panasonic Projectors Immersify Kuala Lumpur

- Elevating Immersive Art to New Heights: GeoBox in Hyundai Futurenet’s Le Space

- Immersive Multimedia Installation at Museo del Lago – Montemurro (Italy)

- Digital art for Karuizawa New Art Museum's special exhibition"Irreplaceable Things - Earth, Landscape, and Environment"

- How To Enhance Museum Visual Experience with Immersive Projection Technology

- Museums in the Digital Era: Tackling Challenges and Learning from Teylers Museum (NL)

- GeoBox Enhancing Historical Landmarks with Immersion: Fort Victor Emmanuel (France)

- A Journey into Immersive Aquarium: The Deep (Hull, UK)

- 125 years BOSCH in the UK: Powered by GeoBox and Panasonic

- Immortalizing Media Heritage In the Media Museum (Hilversum, NL)

- Media museum Sound & Vision in the Netherlands

- Dive Into History with Geobox (Brugge, Belgium)

- Immersive projection installation in Switzerland

- GeoBox support Slovakia Pavilion in EXPO2020

- Experience F-16 at National Military Museum (Soest, Netherlands)

- Mori Building Digital Art Museum: Epson teamLab Borderless

- The 10th annual Korea Gyeongju World Culture Expo

- Projection mapping for museum

- GeoBox recreates the Fifth Aztec Sun at Stuttgart’s Linden Museum

- Discovering the image control solution behind Digital Art Museum

- Show all articles (5) Collapse Articles

-

- Esports AV Integration at Its Best: GeoBox Powers the ZOWIE Gaming Experience Center

- Elevating Immersive Art to New Heights: GeoBox in Hyundai Futurenet’s Le Space

- GeoBox Transforms Interior Design through Immersive Technology (Andalusia, Spain)

- Lifesize Plans - Revolutionizing Architectural Visualization

- Immersive Fusion: The Technological Creativities of Ragdale Hall Spa's Thought Zone

- Illuminating Hope: The Hanbit Tower Christmas Project of (Korea, 2020)

- GeoBox Projection Mapping in Japan Kyoto Kodai-ji Temple

- Elevating the Shopping Experience: IKEA's Immersive Technology in the Heart of Paris (France)

- 125 years BOSCH in the UK: Powered by GeoBox and Panasonic

- Sony Professional Display at OMR 2023 (Hamburg, Germany)

- The Holodeck: A Futuristic Meeting Space

- How G413 elevate guest experience at the luxurious Andreus Resorts

- Immersion in Yoga studio

- GeoBox adds edge-blending interaction to Vodafone’s flagship store in Netherland

-

-

Technical Articles

-

- MSFS 2024 Meets GeoBox M813: The Ultimate Guide to Immersive Flight Simulation

- How to use ChromeBox for Immersive display

- How To Enhance Museum Visual Experience with Immersive Projection Technology

- S902, Improve the effectiveness of your large display system

- Simplify your content preparation workflow with GeoBox

- A Guide for Effortless Immersive Experience Setup in 5 Minutes

- The Synergy of Using BrightSign Player with GeoBox video Controller

- Seamless Edge Blending: GeoBox's Black Level Uplift Solution for AV Professionals

- GeoBox New 810 Series: Elevating Pro AV Excellence

- Synergy of Digital Signage Player and Video Controller

- HDMI Technologies and Cables: A Guide for Professional AV Technicians

- Unveil GeoBox mini edge blending and warping box: G111 / G112

- The new range of All-In-One edge blending solutions - M810 series

- GeoBox in ISE2022

- G901, all-round multi-purpose controller: Multi-viewer, ultra-high resolution, 3D, Seamless switching & more..

- A better solution for your multi-projector edge blending project

- 8K input timing support in all GeoBox solutions

- How to display a large image using multiple projectors?

- Epson x GeoBox 8K/4K demo event

- 4K projectors edge blending and warping

- 4K projector edge blending, warping controller

- Immersive display solution

- How to plan for a large projection system?

- GeoBox G901 4K60hz input and output processor is now available in Europe

- Projection mapping for museum

- Projection mapping technology from GeoBox

- Edge blending calculator for multi-projector project planning

- Reliable Hardware-Based Video Processing for Professional AV Installations

- Show all articles (13) Collapse Articles

-

- How to use ChromeBox for Immersive display

- Digital art for Karuizawa New Art Museum's special exhibition"Irreplaceable Things - Earth, Landscape, and Environment"

- S902, Improve the effectiveness of your large display system

- Simplify your content preparation workflow with GeoBox

- The Synergy of Using BrightSign Player with GeoBox video Controller

- Synergy of Digital Signage Player and Video Controller

- HDMI Technologies and Cables: A Guide for Professional AV Technicians

- GeoBox in ISE2022

- G901, all-round multi-purpose controller: Multi-viewer, ultra-high resolution, 3D, Seamless switching & more..

- 8K input timing support in all GeoBox solutions

- 4K in-out Video wall controller with Multi-viewer - 'world first'

- Video wall controller: Top 5 reasons why using it

- GeoBox G901 4K60hz input and output processor is now available in Europe

-

News Letters

Optimizing Medical 3D Visualization

Executive Summary

Who this is for

Clinicians, researchers, and educators who already use 3D visualization and are looking to improve display reliability and consistency.

Key takeaways

- In mature medical 3D workflows, the main challenge is no longer image quality, but display behavior.

- Depth perception, hand–eye confidence, and teaching effectiveness depend on stable and consistent stereoscopic presentation.

- Different medical devices handle 3D differently, making real-time 3D format adaptation across devices a recurring and practical requirement.

- Optimizing the display layer allows 3D content to move reliably between research, surgical, and educational environments—without altering medical data.

As medical 3D moves from adoption to refinement, reliability and consistency across devices define real value.

Display Stability, Depth Consistency, and Clinical Confidence

Three-dimensional (3D) visualization is no longer new in medicine. Across surgery, research, and medical education, 3D has become a daily working tool rather than an experimental technology.

As adoption matures, the key question for frontline professionals has shifted. It is no longer whether 3D works, but: Whether 3D visualization remains stable, consistent, and trustworthy in real clinical and educational workflows.

For clinicians and educators who already rely on 3D, progress no longer means adding more technology.

It means refining what is already in place—particularly at the display level, where visual behavior directly shapes user experience.

When 3D Becomes a Daily Clinical Tool

In medical environments, 3D visualization serves a very different role than in demonstrations or presentations.

It is used for:

- fine, visually guided manual tasks

- long sessions requiring sustained concentration

- shared viewing in teaching and collaborative settings

Under these conditions, limitations rarely appear as obvious failures.

Instead, users may gradually notice:

- subtle changes in depth perception over time

- increasing visual fatigue during prolonged use

- variations in how different viewers perceive the same 3D content

These experiences often lead to an important realization:

even with excellent imaging quality, the display system itself strongly influences how 3D is perceived and trusted.

Practical Observations from the Front Line

In real medical practice, 3D is rarely confined to a single use case. A professor actively working with 3D technology typically moves between multiple roles—researcher, clinician, and educator.

One key insight emerges from this experience:

The requirements for 3D visualization change significantly depending on the usage context.

Understanding these differences is essential for meaningful optimization.

The following three scenarios reflect the most common and representative ways 3D is used in practice.

3D Visualization in Personal Research: Professional 3D Monitor × PC or Laptop

In personal research settings, 3D visualization is often used for extended periods by a single viewer. The work involves careful observation and interpretation of fine anatomical structures.

In this context, the main technical challenges are not resolution or color, but:

- whether depth perception remains stable over long sessions

- whether the stereoscopic effect feels natural and comfortable

- whether visual behavior remains consistent across different workflows

Small inconsistencies may go unnoticed at first, but over hours they can accumulate into fatigue or uncertainty, ultimately affecting interpretation quality.

“In research, I don’t want to think about the display at all. If the depth perception changes or I need to adjust settings, it immediately breaks my concentration.”

In research settings, 3D content often needs to move between different software environments and display devices. Without real-time stereoscopic format adaptation, researchers are forced to manually adjust display behavior, disrupting otherwise focused analytical work.

In this scenario, an ideal display system effectively disappears into the background, allowing the researcher to focus entirely on the content rather than the display itself.

3D Extension in Surgery and Laboratory Environments: ZEISS Microscope × Large Display

In surgical and laboratory settings, the core 3D imaging often comes from highly advanced and costly medical equipment, such as high-end microscopes.

Here, the role of the display system is not to replace the microscope, but to extend its native 3D visualization to larger displays for collaboration, observation, and teaching.

The key challenges include:

- whether the original depth relationships are preserved when displayed at a larger scale

- whether the operator and observers perceive the same spatial structure

- whether display behavior subtly influences confidence during procedures or explanations

When 3D output from a surgical microscope is extended to displays of different sizes and types,

the absence of real-time 3D format adaptation can unintentionally alter spatial relationships that were originally highly reliable.

“The microscope already gives us a very reliable 3D view.

The challenge starts when we extend that view to a larger display for others in the room.”

The task of the display system is therefore very specific:

to preserve, rather than alter, the original 3D experience created by the medical imaging device.

3D Consistency in Teaching and Lectures: Laptop × Projector

Teaching and lectures are often the most underestimated 3D use cases, yet they are among the most sensitive.

Here, the challenge is not individual operation, but shared understanding:

“When I teach in different rooms, I want students to see the same 3D structure I’m explaining, not a slightly different version each time.”

- whether all students perceive the same spatial relationships

- whether 3D content behaves consistently across different classrooms and projection systems

- whether gestures, pointing, and spatial explanations remain clear

Even with identical content, variations in display environments can lead to differences in comprehension.

In educational settings, the role of the display system is to ensure that:

- stereoscopic visualization remains repeatable across locations

- teaching quality is not compromised by display inconsistencies

For medical education, this consistency is critical.

Three Scenarios, One Recurrent Limitation

At first glance, these three scenarios appear very different. Yet in practice, they repeatedly expose the same limitation:

3D visualization does not behave consistently across different devices.

Professional 3D monitors, surgical microscopes, and projection systems often rely on different stereoscopic formats and output methods.

Each system may work well on its own, but difficulties arise the moment 3D content needs to move between them.

In daily medical workflows, clinicians and educators routinely transition between:

- personal research workstations

- surgical or laboratory imaging systems

- teaching and presentation environments

Without real-time adaptation, these transitions commonly result in:

- mismatched stereoscopic formats

- inconsistent depth perception

- additional manual configuration or workflow interruptions

For medical users, this is not an abstract technical concern. It directly affects efficiency, confidence, and continuity when working with 3D visualization.

The Need of Real-Time 3D Format Adaptation Across Medical Systems

To address this recurring limitation, a dedicated 3D processing platform is used to perform

real-time adaptation between different stereoscopic formats, without altering the medical image itself.

By handling format differences transparently, such a platform allows clinicians and educators to:

- move 3D content seamlessly between devices

- preserve consistent depth perception

- avoid workflow disruption when switching environments

This capability is especially important in medical contexts, where 3D visualization is not confined to a single room, device, or purpose.

Defining the Role of Display Optimization

Clear role definition is essential in medical environments. Display optimization platforms are not medical devices:

- they do not diagnose

- they do not make clinical decisions

- they do not alter medical data

Their contribution lies in visual reliability and consistency. When display behavior is predictable and stable, clinicians and educators can focus fully on interpretation, practice, and teaching.

From Adoption to Refinement

For medical professionals already using 3D visualization, meaningful progress often comes from refinement rather than expansion. As medical 3D continues to evolve, attention shifts from whether to adopt toward:

- long-term stability

- perceptual consistency

- sustained confidence in what is seen

This transition marks the mature stage of medical 3D visualization, where reliability, not novelty, defines value.

From Practice to Reference

GeoBox Unveiling the Future of Neurosurgery with 3D Technology: Interview Professor Wolfsberger (Austria)

Related Tools for Medical 3D Visualization

The following tools are commonly used to support stable and consistent 3D visualization across medical environments.

They are not medical devices and do not interpret clinical data. Their role is limited to display behavior, stereoscopic consistency, and real-time adaptation between different 3D systems.